- Home

- Zarreen Khan

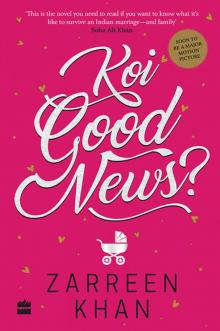

Koi Good News?

Koi Good News? Read online

Table of Contents

Week LMP (Last Menstrual Period before pregnancy) minus 4

Week LMP minus 3

Week LMP minus 2

Week LMP minus 1

Week LMP

Week 2

Week 3

Week 4

Week 5

Week 6

Week 7

Week 8

Week 9

Week 10

Week 11

Week 12

Week 13

Week 14

Week 15

Week 16

Week 17

Week 18

Week 19

Week 20

Week 21

Week 22

Week 23

Week 24

Week 25

Week 26

Week 27

Week 28

Week 29

Week 30

Week 31

Week 32

Week 33

Week 34

Week 35

Week 36

Week 37

Week 38

Week 39

Week 40

Week 41

The baby

Kabir

Acknowledgments

About the Book

About the Author

Copyright

For Kyrah, Zayn and Iram

Week LMP (Last Menstrual Period before pregnancy) minus 4

A woman’s fertility begins to decline after the age of thirty

Mona

The most chaotic afternoon ever in the Amritsar household.

Had to spend three and a half hours with Daisy chachi, trying to convince her that Nishi bua had not stolen her outfit design on purpose. Daisy chachi is distraught. Apparently she had the chungi ka tailor spend weeks copying the design she saw her daughter-in-law’s sister’s mother-in-law wear at a wedding in Delhi. And now the so-called evil Nishi bua has got herself the exact same outfit made and is planning to wear it tonight.

We had to drag Daisy chachi out of the room before her verbal assault turned physical, while Nishi bua sat unperturbed, tying up the little bags of besan ke laddoos, which are to be sent to the boy’s side tomorrow as shagan.

I’m not sure why Mummy left me in charge of pacifying the volcanic Daisy chachi (perhaps because I’m the only sensible woman in this family), but there I was, locked up in my room, making sympathetic tutting noise to calm down a furious Daisy chachi. She’s been watching a soap too many on Star Plus, if you ask me. She believes it’s some grand Deol family saazish against her, because at cousin Mohini’s engagement, she wore the same polki set (which we know was fake) that Nishi bua wanted to wear (which we also know was fake). So this, she believed, was Nishi bua’s way of taking revenge.

They both hate each other. Have for years. It started out during their schooldays, when both Nishi bua and Daisy chachi harboured ‘feelings’ for the same rich halwai ka beta, who kept them both hanging, only to marry that Jams and Cakes wale ki daughter, leaving them both heartbroken, and locked in some everlasting competition. Mummy’s told me all about it. Mummy claims she’s not one for gossip, but one week of being married into this family and I knew my mother-in-law was bursting at the seams with ‘information’.

So un-school-principal-like. That’s what she was till last year, my husband Ramit’s mother. Principal of an all-girls convent school in Amritsar. I’ve never met someone who looks the part more than her. She’s always in these starched cotton saris, with perfectly pleated pallas, big bindi on her large forehead, glasses atop her head, hair in an oh-so-school-teacher-type ‘blunt cut’. Very unlike my own mother, who’s petite and disorganized, her frizzy hair pulled back in a messy ponytail, paddling around in her unmatched salwar-kameez suits. She looks quite ‘bechari’. Highly deceptive, of course. Because she’s really just as much a tigress as my mother-in-law.

For two whole hours, Daisy chachi bored me with her theories and even hinted at Mummy being a part of the conspiracy, till Mummy walked in and scorched her with one solid principal-like stare. No one messes with Mummy.

Anyway, after a while, they settled for a truce, since it is, after all, apni Chiku’s wedding. A somewhat friendly compromise to wear matching outfits tonight has been reached. It will now be a battle of who’s pairing it with better jewellery – and who’s looking slimmer. Daisy chachi has scurried off with her daughter-in-law to the locker. And for liposuction, maybe.

I should’ve expected it, though. It’s a Deol wedding. Deol weddings are loud, boisterous, often violent and always a circus.

Four years ago, at my own wedding, I was nothing less than horrified to discover that my lovely, docile, serious Ramit belonged to this Sooraj Barjatya consortium. Sixteen first cousins. Twenty-two second cousins. God knows how many thirds. And that’s only on the paternal side. Everyone we meet on the Amritsar streets is somehow related to us. Bua’s husband’s cousin’s son. Maasi’s daughter’s husband’s brother. Cousin’s mother-in-law’s sister’s husband. They don’t have a family tree. They have a family forest.

Ramit calls the cousins ‘bheed’. I thought it was pretty rude initially, but there’s no other way to describe it. The rhyming names, the cacophony of guttural laughter, the free-flow of alcohol, the non-stop cricket in the driveway, the daily fashion show. They’re all just loud, happy Punjabis. We are, I mean. I am one of them now.

Anyway, back to the point … after the truce, we returned to meet the inflow of relatives arriving for Chiku’s wedding, and I was subjected to a fresh bout of the same conversation: arrey! Looking nice and healthy! Looking fully Punjabi like us now! Where is Ramit? What are you doing nowadays? When are you ‘planning’?

Planning. How I’ve come to hate that word.

After all, four years of marriage and no baby. No ‘good news’.

And Ramit has sent me here to face this ALONE!

Ramit

Eight texts. In one hour. While I’m in a meeting with a client.

I’d told Mona to message me only if things were urgent.

And there are eight messages. In one hour.

Finally, had to put my phone on silent after Surjit shot me a ‘pay attention’ look.

I have to stop feeling guilty about sending her to Amritsar alone.

Mona

Chill? Chill??? That’s all he had to say???

Sent him another one:

Eight people have asked me the question. Eight! Koi good news? Somesh tayi even ran her hand around my paunch saying bata bhi de. I know I’ve put on a little bit of weight but to mistake it for a baby? Then Nishi bua asked whether we are planning. Then Suttu asked. Suttu, aged eighteen, who should be concentrating on her exams rather than our ‘good news’! Then some neighbour I’ve never seen before asked me if I was Kavita’s bahu, the Delhi one, who doesn’t have any children yet. That’s how they describe me! How could you send me here alone? How could you? And don’t you ever say chill to me again!

His response after five whole minutes: k

And then nothing.

I stuffed my phone into my pocket after that. There is no point in fuming over it. Because it’s Ramit.

For four years I have had the sole responsibility of keeping conversations alive in our household. When he gets back from office, I tell him everything that has happened in my life. Everything. The maid came. The maid said. The maid cooked. The maid complained. The maid quit. Mom called. Mom said. Mom complained. Mom slammed the phone down. Mummy called. Mummy said. Mummy complained. Mummy advised.

Ramit’s response: K

He doesn’t even bother with prefixing an O any more!

Now that’s us: I talk. He says K.

Was it like this when we weren’t mar

ried? I can no longer remember. He was never much of a talker, but to be reduced to a single alphabet? Most days, he stays buried in his phone or his laptop, his mind on his newly set-up business and his conversations as crisp as his business emails. It’s like he has no emotions.

I told him exactly that, though in slightly more detail, through yet another SMS, and hit SEND right before Dadi called me for a status update on the Daisy chachi–Nishi bua brawl.

Ramit

Yet another message from Mona. She was conned into a meeting with Dadi, supposedly for a conversation on some sort of fight chachi and bua were engaged in, but it turned out to be a conversation on our family planning.

Advanced my tickets to tomorrow lest my family becomes the reason for my divorce.

Mona

I wish I could be more like Ramit at times like these. Ramit would’ve just said ‘no plan’ and walked off. I just sat there, red-faced. But then to be fair, these conversations embarrass Ramit more than they embarrass me. It also shows a whole lot more on his Punjabi complexion.

Oh these conversations!

When we married at the ripe old-age of twenty-seven, we thought we had finally escaped the ‘when are you getting married’ phase. But waiting for me – for us – on the other side, was the dark demon of ‘good news’.

Ramit would snap, saying, ‘We just got married, isn’t that enough good news?’ But apparently wedding toh honi hi thhi. Now give us the ‘real’ good news – that your reproductive organs are working.

We skirted the issue pretty successfully initially ... or so feels the innocent-to-the-extent-of-being-dumb Ramit. I, of course, disagree.

We used a gamut of excuses.

Abhi hum ek doosre ko jaan le: Which was, okay, a slightly lame excuse. We had a love marriage. But trust the Deols to come back with the clichéd ‘you have the rest of your life to get to know each other.’

Abhi humari umar hi kya hai: A fairly valid excuse at twenty-seven. Apparently not at twenty-eight. Not only is my biological clock ticking, it is also a point of prolonged discussion.

Abhi humein duniya dekhni hai: Okay, fine, that does sound like Kajol from DDLJ. We heard a lot of gasps at that one. How dare we put ourselves before their to-be grandchild/niece/nephew! I think Ramit’s Dadi fainted.

Abhi hum financially stable nahin hain: We seriously couldn’t afford a kid. We always got a: ‘So what? We couldn’t afford kids either. In fact, we didn’t even get as much salary as you guys do nowadays.’ Which is seriously rubbish! Delivery at their times would cost them 200 bucks and it now costs you 2,00,000.

The truth is, we really didn’t want kids till last year. Ramit was setting up his business, we were staying in a rented house, and we had very little saved up. The idea of the expenses that come with a baby scared us. Not to mention the responsibility.

There were some people who were kind enough to say: ‘It’s only your first year of marriage – enjoy yourself.’ I actually fell for this sugar-coated talk. They were the first ones to call us on our first anniversary and say, ‘Ab toh khoob enjoy kar liya. Ab toh good news suna do.’ Clearly our ‘enjoyment’ needed to end by giving them ‘good news’ quickly!

And in our second year of marriage, every Tom, Dick and Harry believed it was their right to discuss our sex life. And of course, it’s only out of kindness and concern regarding our conception issues. Because we guys do have conception issues, right? No other reason we’re not reproducing?

So be it the aunts and uncles or the bhabis and chachis, or the maids who stopped whispering the minute I entered the kitchen, or even the colony aunties whose main occupation otherwise is to stand in their balconies displaying their non-dupatted cleavage and whose claim to fame had been Bittu-ke-papa getting them pregnant within two months of their marriage – my baby-producing skills were being questioned at large. And still are.

And there was the biggest issue of it all – being a Deol. The Deol family of Punjab is as fertile as the soil they sing songs about. We seem to have broken some generation-old tradition by not reproducing almost immediately after marriage. Since Ramit is a Deol, obviously the fertility problem can’t lie with him. So it’s me who everyone reserves those looks for.

Ramit

We couldn’t afford to have kids. Period. Don’t know why Mona can’t tell them exactly that.

Sometimes I wish I had warned her about the bheed before we got married. To think of it, it was slightly evil to get Mummy-Papa to meet Mona and her family in her house in Dehradun rather than let them come and see the wildlife resort we live in. Mona had innocently thought that since I was the only child, it was just Mummy-Papa and me.

But then again, Mona should have understood when I told her the baraat would be 500 people, and that it was best we had the ceremonies in Amritsar. What did she expect? 500 friends?

Mona

So finally I’m meandering my way through the bheed, carrying in my arms the mewa ki dibbis that Chiku wants us to distribute during the pheras like she saw on some Pakistani show, when Mohini arrives with her post-honeymoon glow, her sindoor running down her forehead, her chura clanging as she hugs the junta and then, red-faced, announces she’s pregnant.

My brain goes into overdrive. How! She has only been married one and a half months! I’m sure they’d been up to something before the wedding, otherwise there is no way this could have happened. I steal a glance at Mummy, who’s clearly frozen in shock. She’s probably mulling over the same conspiracy theory. Then I realize that a lot of people are stealing glances at me in return. I suddenly felt very hot.

Toshi, the only one in the same boat as me, since she hasn’t given ‘good news’ in the one year she’s been married, (though she’s twenty-five, and six years younger than me) tells me in hushed tones, ‘Arrey! Kya jaldi thhi? Can’t they keep their hands off each other?’

But I think Mummy’s had enough now. She takes me up to my room, shuts the door discreetly, sits me down, wears her best school-principal expression and asks me seriously what the ‘progress’ is. I am mortified by these conversations. I keep thinking she is picturing me having sex. She’s even told me a couple of times how I need to ‘enjoy it’ and not stress about getting pregnant. Enjoy it! Those were her words.

So after turning multiple shades of red, I say the worst thing one could possibly say: ‘Nothing.’

‘Nothing!’ she gasps, clutching her chest dramatically. ‘You are planning, aren’t you?’

Since all I can manage is a nervous ‘well …’, she explodes.

‘Well? Mona! Ramit and you have been married for four years now. First he said he wanted to concentrate on his career. We didn’t say anything. Then you left your job and we didn’t want to put pressure on you. But beta, now you’re thirty-one years old! Girls have a biological cycle, you know.’

I want to tell her that yes, I do know, I passed ninth-grade science, thank you very much. But she’s Ramit’s mother. I can’t say that. I just sit there, twirling my dupatta around my finger anxiously. But, I think I kind of understand the type of pressure she feels, with the other relatives asking her when she’s going to start her grandparent quota. And Mummy does have our best interest in mind.

I think she does. Maybe.

‘You know,’ she looks around the room, as if to ensure that no one is eavesdropping, ‘Perhaps you should go see a doctor …’

I twist my dupatta even tighter around my finger.

‘You’re both happy, aren’t you?’

Not being able to produce a kid is clearly a mark of not being ‘happy’. I want to say something, I really do, but being with Mummy is like being in the principal’s office. Words bounce around in your brain and nothing appropriate ever makes it to the lips.

I can’t get myself to say a single word. Finally, she pats my knee.

‘Ab kar lo, beta. Ab toh tumhara apna ghar bhi hai.’ Yes, like we hadn’t been having sex because we were living in a rented flat!

Then follows the lecture that I d

utifully nod along with, and as soon as it finishes, I run out at full speed. And promptly bump into the newly pregnant Mohini. She gives me a look of such sympathy that I feel like strangling her!

Ramit

Almost choked as Shaan, Swaroop, Abhiroop and a couple of their friends engulfed me at the airport. They took me directly to sheher to have some Babbu ka mutton tikka. We watched as Babbuji slashed open a 200gm pack of Amul butter and flung it on the sizzling pan. A bead of sweat dripped into it and only when that crackled did he know that the pan was hot enough for the mutton. Using a rusted knife, he hammered the chops and pushed them into the pool of darkening butter. Then he picked the dirtiest cloth available, used it to wipe a steel plate and plopped the cholesterol on it. I swallowed a rush of acid that rose to my mouth along with my pride. My cousins seemed unaffected, and I couldn’t have them think I’d become a fussy dilliwala.

Smacked my fingers and made the appropriate appreciative noises, then got some packed for Mona for effect. The cousins clapped me on my back and we had decided the batting order for our gully cricket match before we even got home.

Mona

Yesterday, right before the sangeet, I had terrible acidity (bloody Babbu’s mutton tikkas!) and spent the evening throwing up. I was totally offended at how much joy my sickness was giving people. I had just about returned from my first bout when an excited cousin, Suttu, went running to tell everyone I was throwing up. The room was suddenly flooded with thrilled-looking people. It broke up a game of cricket – that’s how serious it was. Everyone asked me to lie down with my feet up and not take any medicines. I didn’t get it at first. How naïve could I have been!

I had to throw up another couple of times before they let me have half a Digene. I think I heard some people congratulating Mummy as well. Ramit was as confused as I was. He was the only one who kept asking me what I’d eaten – everyone else sniggered at his question!

When Ramit and I were finally left alone, he asked me gently if I were sure I was not pregnant. I opened up my bag and thrust the half-empty pack of Whisper Ultra in his face. ‘I’m currently using these. What do you think?’

I didn’t care how awful I felt, I had to attend the bloody sangeet to make a point.

Koi Good News?

Koi Good News?